“It was announced one morning, and in the next week, we were gone,” Social Studies Teacher Lanting Xu said. “My parents were gone. We started living with this family.”

Xu was born in Beijing, China, three years before Chairman Mao Zedong took over and began the Cultural Revolution. When Xu was just 6 years old, her parents were sent to the countryside for reeducation.

In short, the Cultural Revolution was a Communist movement, which looked to restructure society by forcing the intellectual class to be reeducated by the proletariat class. The goal was to simplify life and completely restructure Chinese society to remove the inequality of capitalism.

“Every day on the radio, we would listen to … Chairman Mao’s instructions,” Xu said. “Every day, [my dad’s] friends would be calling him: ‘come down, Chairman Mao has a new instruction. Let’s go celebrate.’”

Xu’s father, who worked for the National Theater, was sent to a military base along with everyone else with whom he worked. Her mother was sent to a different area of the countryside.

They were relocated only because of their status as intellectuals.

Xu, at 6, and her sister, who was 7, were left without parents. They moved to a different area of Beijing to live with a family friend who had taken care of her sister when she was younger.

She lived with this new family for three years while attending elementary school. During this period, she never saw her father, and only saw her mother around once a month.

The teenagers were in these collective farms. Many of them suffered mental illness, and many of them were killed, especially those who worked in the timber industry. They didn’t know how to cut the tree. They just stood on the wrong side, and then just got crushed.

— Social Studies Teacher Lanting Xu

However, Xu became homesick, as she wasn’t close to the family who took care of her.

“They were very close to my sister, obviously, so I was a complete outsider in that picture,” she said.

When Xu was 9 and her sister was 10, they spoke with their mom and decided to move back to their previous home. Simultaneously, there was a change in policy, and Xu’s mother was allowed to go home and live with them.

Still, Xu saw her mother sparingly.

“We rarely saw my mom anyway, because she left to work really early in the morning and came back really late at night,” she said. “Periodically, she still had to go to the countryside to help out with different things.”

Xu said she grew up practically alone at home, but she was very close to the other kids living in her neighborhood. Also, the older kids were able to look after the younger ones in her community.

“We were lucky to live in this complex organized by the National Theatre,” she said. “Every child in that complex was in the same situation as us, so there were about 40 kids living in the complex. We all kind of hung out together, spent after school time together, played together and also took care of each other.”

Although Xu said that her childhood was unusual, she recognized how living alone helped her become more mature.

“In a way, it did help us to be very independent and self-disciplined, simply because there wasn’t anyone there to tell you what to do,” she said.

Living with such little parental connection, Xu said all of the kids in her neighborhood didn’t develop strong relationships with parents.

“That experience really created a very different human relationship for us,” she said. “We were just not very close to parents.”

Xu said she saw her father maybe three times in five years from when she was 9 to 14.

While attending primary and middle school, Xu’s education not only included common subjects such as math, but also integrated recitations of Chairman Mao’s sayings in the curriculum.

“You basically learned very quickly how to articulate your thought within the Party framework,” she said. “You know exactly what keywords and buzzwords to say in your speech and in your writing. You learn very quickly the formula you need to follow in your writing. You learn how to toe the Party line, so that you’re consistent with that idea.”

Xu said some of the common instructions she would have to say were “never forget the class struggle,” “revolution is not a dinner banquet, revolution is violence,” and other sayings similar to those.

As time continued under Mao’s rule, Xu experienced some of her older friends who grew up at the same complex as her being sent to the countryside for reeducation, as colleges were outlawed during this period.

Xu noted a level of poor mental health among youth who were sent away.

“You just get those rumors of ‘so and so being sent back last night. Why? Because she swallowed several needles trying to commit suicide,’” she said.

Along with mental health issues, people lacked experience in their forced labor and, therefore, had complications.

“[The teenagers] were in these collective farms,” Xu said. “Many of them suffered mental illness, and many of them were killed, especially those who worked in the timber industry. They didn’t know how to cut the tree. They just stood on the wrong side, and then just got crushed.”

Xu said she heard a lot of these “horror” stories growing up.

“It was not a good picture at all,” she said. “It was very sad. Suicide was very common among those really young people sent to the countryside.”

Life after the Cultural Revolution

“There was this fear around going to the countryside,” Xu said.

Xu never had to experience the forced labor in the Chinese countryside because the Cultural Revolution ended in 1976, right before she entered high school. Just a year later, colleges resumed, so she knew she had a future in higher education.

“We were the lucky generation,” Xu said.

After graduating from high school, Xu said she spent a lot of time reflecting on the society in which she lived. She said her first few years in college were a time for her to “somehow purge myself of all the kind of brainwash and propaganda that I had acquired or accumulated during the revolutionary era.”

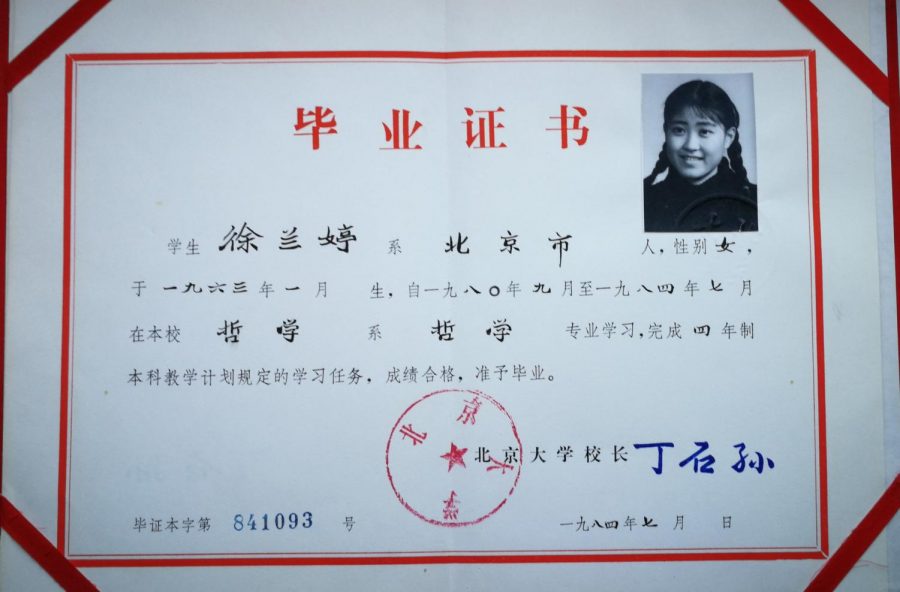

Xu spent seven years at Peking University in Beijing, China. While there, she first became exposed to Western philosophy, and, as a result, Xu was able to develop new ways of analyzing the world. She said that her time at university was “perhaps the most freedom Chinese people had ever experienced in terms of the freedom of speech and freedom of thought.”

“Lectures were given, discussions were hosted,” she said. “Therefore, you really had that kind of exposure to a variety of things.”

Social Studies Teacher Lanting Xu when she graduated from Peking University.

After her time at Peking University, Xu started to teach at Beijing Normal University and volunteered in a nonprofit agency called the Academy of Chinese Culture, which provided a general education on traditional Chinese philosophy and values.

During this two year stint, Xu witnessed first-hand political unrest in the region.

Most notably, Xu saw the Tiananmen Square protests and the government crackdown that occurred in 1989.

“In 1989, I was already working for two years, but every time I went back home from my work, I would pass by the Tiananmen Square, and I could see the protesters over there,” she said.

“On June 4, [1989], there was kind of a series announcement throughout the day about staying at home,” she said. “Some kind of military order had been given. We could see military moving into places near Beijing.”

“Throughout the night, we could hear gunshots, which was scary because Beijing as a city, even when the communists took over Beijing, it was a peaceful transition. There was not one single shot made. And that was the first time in 1989 under communism. The citizens in Beijing, for the first time, heard gunshots and saw people killed.”

A year after the crackdown in Beijing, Xu moved to the U.S.

Although Xu said political reasons somewhat inspired her relocation, the main reason was she felt that Chinese society was highly misogynistic.

“The Chinese women tend to be double oppressed,” she said. “On the one hand, they had to compete with men in the workplace. And then, when going back home, they had to perform all the traditional women’s functions: cooking, cleaning, raising children.”

Also, Xu said finding a job was difficult due to derogatory images of women held by employers.

“The companies would say,’ why would I hire a woman who will fall in love, so she wasn’t going to concentrate on the work?’” she said.

Another issue Xu found in the workplace was that she was unable to earn credit for work that she completed.

Similarly, she said men wouldn’t be transparent when dealing with women.

“You could feel all the men trying to take advantage of the fact that you’re a woman, so they kind of lie through their teeth,” she said. “Therefore, I just did not really want to live in a society where you feel like your human potential could not be fulfilled freely simply because all the restrictions given to you by that culture.”

Reflections

After living outside of China for 30 years now, Xu said that misogyny is probably worse in China currently, especially with the growth of the internet. She said this has inspired women to become “kept women”: a woman who acts as a mistress for a rich man.

Xu said that women who choose to do this are not necessarily uneducated and may even have university degrees.

“[Chinese] society now is very complex, and many traditional gender roles are intensified at this point,” she said.

For Xu, these roles are worse now than during the Cultural Revolution.

“Under Chairman Mao, one of the projects for him to bring China into modern society is precisely to liberate Chinese women, so he talks about how women hold up half the sky,” she said. “It was such a model for gender equality for the whole world.”

Also, Xu said she has seen a decline in ethical standards in China compared to those during the Cultural Revolution.

When reflecting on the processes that lead to the cultural revolution, Xu said she remembers the implementation of these ideals was basically through mind control, propaganda and general poverty – what is now called social engineering.

Through this experience, Xu said she learned to be critical of overarching theories on humanity and the attempts to implement them.

“The lessons for me through this process was really to understand the danger of any attempt of social engineering,”

“It taught me to be skeptical of any simplistic and reductionistic picture of the world, especially the human relationship, because you know that human relationship, even throughout the Cultural Revolutionary Era, is much more complex. No one is so black and white. And then you start to see things in more like shades in these complexities.”

With this lens on life and society from her childhood experience, Xu said she has found issues with today’s era of political correctness due to its over-labeling of individuals.

“I see the tendency of certain groups of people who really relativize all possible values in the name of identity, equality, diversity, multiculturalism … as if every single value every single practice has equal value,” she said. “In the case of China … that way of thinking can be quite dangerous for a society.”

Xu said she feels there’s an urge to exert identity politics in today’s world, which can over-label people to have a larger presence in society.

“I’m not entirely sure whether that creates a cohesive force that would be more inclusive to all people or actually if it creates more divide,” she said.

Because of her experience growing up in the Cultural Revolution, Xu said everyone must avoid shaping individuals’ identities based on generalizations.

“The lesson from the Cultural Revolution is … that all of us should have the freedom to embrace whichever identity in whichever life aspect we so choose,” she said. “Therefore, every one of us is a complex whole and … no generalization can be placed.”

When Xu considers diversity in relation to the school community, she said she sees the irony in claiming and embracing diversity because it creates a “more homogeneous culture where people are further pigeonholed.”

Xu said the school should move away from the idea of outward inclusion and, instead, focus on allowing people to choose to include themselves.

Xu said this feeling comes from an initial sense of exclusion, and that inclusion becomes a problem only because we exclude.

Moving forward, Xu said there should be an overarching sense of inclusion as soon as one becomes associated with the school.

“To tell people, ‘you know what? the precondition of you being here is that you’re already included,’” she said. “‘The rest is for you to pick and choose.’”