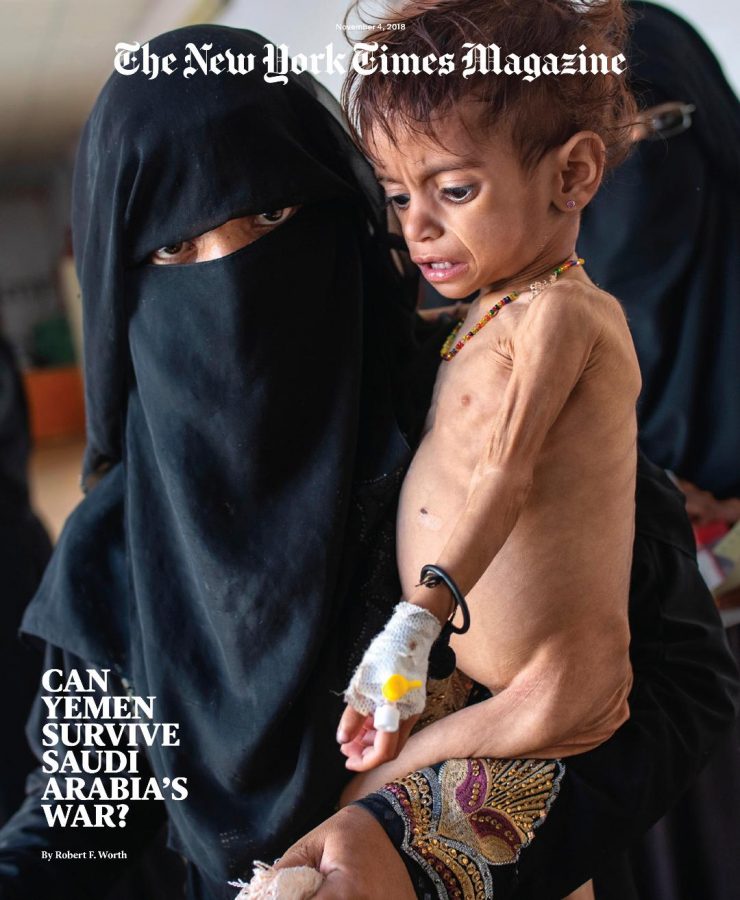

Photo used with permission from John Moore/Getty Images

Photographer Lynsey Addario stands near the frontline during a pause in the fighting while covering the popular uprising for The New York Times, March 11, 2011 in Ras Lanuf, Libya.

Lynsey Addario: I have been kidnapped. Twice.

Lynsey Addario’s (P’30) work often takes her to the frontlines of war. She explores international relations behind the lens of her camera, with a special focus on the role of women in more conservative societies. Addario also has a husband and son at the school. Currently, the Pulitzer Prize winner is covering COVID-19 by photographing ICUs and hospitals to share the experience of healthcare workers with the world. After the pandemic is over and travel is permitted, Addario plans to use her National Geographic grant to photograph women and climate change in five different countries around the world.

In her words:

I grew up in Westport, Connecticut, in a household that wasn’t very intellectual. I was raised by hairdressers – everyone was very creative, but we never really had a big bookshelf full of books. My parents never said, “Do this, do that.”

I was into photography – I loved the idea of light and capturing a fraction of a second of time – but I never connected the dots that photojournalism was a way to incorporate current events within art.

— Lynsey Addario

We didn’t get the New York Times or any newspapers in our house, so as a result, I wasn’t really familiar with photojournalism as a profession. I was into photography – I loved the idea of light and capturing a fraction of a second of time – but I never connected the dots that photojournalism was a way to incorporate current events within art.

I went to [the] University of Wisconsin, and there I studied international relations. When I graduated the only thing I wanted to do was take photos and learn Spanish. So I moved to Argentina to study Spanish and to have some sort of freedom to do what I wanted.

I just started photographing a lot on the streets, and I started to become aware of pictures in the newspaper. It sounds crazy, but being out of my element, I was much more aware of things that I hadn’t been aware of back at home. So I went into the Buenos Aires Herald, which was the local English newspaper, and I begged them for a job. They were like, “Well, you have no experience, why would we give you a job?” I was so persistent. I basically just kept going in until they were so annoyed they gave me the job.

I stayed there for almost a year and just photographed and started to learn how to take pictures for the newspapers and for media. Then I moved back to New York where I started freelancing for the Associated Press. I really learned [there] because I had great mentors.

What makes a good picture has to do with intimacy. It has to do with content, what’s actually included in that picture. Something as simple as the light, is the light beautiful? It’s a combination of things where, as a photographer, I’m constantly thinking about as I’m looking through the camera. How can I bring someone into the scene with me? It has to be captivating. It has to be something they haven’t seen 1,000 times before. That’s hard with photography because almost everything’s been photographed.

I believe that journalism is so fundamental to getting those crises out and for informing the public about the injustices of war and humanitarian crises.

— Lynsey Addario

My whole career has been war and humanitarian crises, and I think my heart is still there. I believe that journalism is so fundamental to getting those crises out and for informing the public about the injustices of war and humanitarian crises. But I do a lot of stories on women’s issues. There aren’t that many female photographers who are willing or who go to very dangerous places. As a woman, I often have very good access to women [subjects]. Maternal health, at this point, I think over 260 thousand women die in childbirth. When I first started those stories, it was 500 thousand women dying every year.

I think I was 26 the first time I went to Afghanistan. They weren’t threatened by me, I looked really young, I was really sincere. I really just was excited about traveling and learning about women in Afghanistan. Being a woman in a part of the world, primarily in the Muslim world, where women aren’t really out in the workforce, people just didn’t take me seriously. It allowed me a lot of access – I was able to access families and women in their homes.

In terms of the more hardcore war stuff, I did a two month embed in the Korangal Valley in Afghanistan with 173rd. Being a woman, it was hard in that I’m physically just not as strong as a lot of my male colleagues. I exercise seven days a week and put a lot of time into being fit because it’s a very physical profession. I mean that stuff is really physically grueling, so I was always sort of scared that I wouldn’t be able to keep up. As a woman, I was sort of very aware of my gender in the sense that I always was trying to prove myself.

I’ve been kidnapped twice. The first time was only for a day, so it wasn’t a huge deal in retrospect, but it was terrifying. I was covering the war in Iraq for the New York Times when the security guys with Blackwater were killed and set on fire and hung from the bridges in Fallujah. It was kind of the Mogadishu moment of the war in Iraq. Things got very dangerous very quickly – we were going down a smuggler’s route and were stopped.

The thing about being held hostage is that you have no control over the situation. We had I don’t even know how many guns to our heads for about eight hours, and we just sort of tried to talk our way out of it: “We’re journalists and we’re here to tell your side of the story.” We were very lucky because our driver was from the same tribe as the men in Fallujah, the insurgents who were holding us hostage. We were shuttled around. We were brought to one of their bases and then to a private home. Everyone was sort of negotiating what to do with us and eventually, we were released.

In Libya, it was much more dramatic. We had been covering the frontline of the war – it was a popular uprising. Because of that, Qaddafi did not want journalists covering the uprising because he wanted to show that he was in power. Libya was a country that had never really had free press, and so Quaddafi was able to say, “Journalists are spies, you shouldn’t trust journalists.” The majority of the soldiers believed whatever he told them, of course.

Each one of us had a gun to our heads and begged for our lives. We were very lucky they didn’t kill us, but for the next three days we were tied up, blindfolded, beaten up, punched in the face, groped.

— Lynsey Addario

One day in mid-March the frontline started moving in, and we knew that we had to leave. We knew the timing was kind of essential, but also as journalists, you want to stay as long as you can because you want the best story. So we stayed, and eventually Quaddafi’s troops overran our position and cut the road in front of us. We thought we were driving away from them, but they were actually in front of us. That moment was just terrifying because we knew that they had been told journalists were spies, we knew we could get arrested and we assumed we would be tortured, if not killed.

There were four of us in the car. Me, Anthony Shadid, Stephen Farrell, Tyler Hicks and our driver Muhammad. We drove up to the checkpoint, everyone was screaming something different, “Stop the car,” “Keep driving,” “Don’t stop.” Eventually, Mohamad panicked and he stopped the car. It was like a free-for-all. All the men were pulled out of the car [and] had guns to them. The rebels we have been covering started open fire on the checkpoint, so we were caught in a wall of bullets. I, as the only woman, was left in the car because they couldn’t figure out, you know, who was I, was I Libyan? So when the shooting started from behind us I knew I had to get out of the car because it wasn’t armored. I made a run for it.

I had to realize that this job not only is about me and the stories I’m covering, but it affects loved ones.

— Lynsey Addario

We all ended up behind this stone building. At that point, we were told to lie on the ground execution-style. Each one of us had a gun to our heads and begged for our lives. We were very lucky they didn’t kill us, but for the next three days we were tied up, blindfolded, beaten up, punched in the face, groped. For me, as the only woman, I was touched repeatedly. It was terrifying because you never know what will happen next. It’s human nature to go into survival mode and be able to deal with whatever’s at hand, but it’s also the fear of what will happen next. Eventually, we were flown to Tripoli and held for another three days, then released after a week. Our driver ended up dying. We don’t know if he was killed in the crossfire or if they executed him, but we never saw him again. He was a kid, I mean, he was a student who was just working with us.

The kidnapping in Libya came at a time where I had been covering war for over a decade. I lost a lot of friends – two or three of my colleagues were killed. Another friend of mine lost both his legs in Afghanistan in a landmine, so a lot happened consecutively around that time. Not only was that experience really profound on many levels for the trauma, but also the fact that it was a turning point. I had to realize that this job not only is about me and the stories I’m covering, but it affects loved ones. I still cover war, I still go to the frontline, but I have to put a lot more time and thought into every time I risk my life in a way I didn’t when I was younger. You think you’re invincible when you’re younger. For me, I thought nothing would happen so long as I focused on my work. It’s beyond naive.

My role is to help express the stories and experiences of the people I photograph and interview. It gives me the chance to educate people, to take people to places that wouldn’t otherwise be able to go.

— Lynsey Addario

Everyone asks me, “Why are you still functioning? Why are you still so happy and such a positive person?” I come from a really solid loving family that gave me so much support and love growing up. My parents were so eccentric and artistic – they never really put pressure on us as sisters. We were four sisters, and they just sort of said, “Follow your creativity and go with that, and it will lead you to a very successful and happy place,” and that’s ultimately what I did. It gave me the resilience and the feeling that I can endure or survive anything. When you look at the studies on trauma and PTSD, a lot of them revert back to how you were raised, and coming from a sense of community helps one overcome trauma. And then rather than bottling things up, I process things in the moment and I talk about them a lot. I think that also helps.

My role is to help express the stories and experiences of the people I photograph and interview. It gives me the chance to educate people, to take people to places that wouldn’t otherwise be able to go. I’ve been to over 75 countries and I think that’s a real privilege. Every one of these trips is incredible. I love people, I love learning about their culture and being able to share that experience as much as I can through pictures and words to an audience. That’s amazing for me.