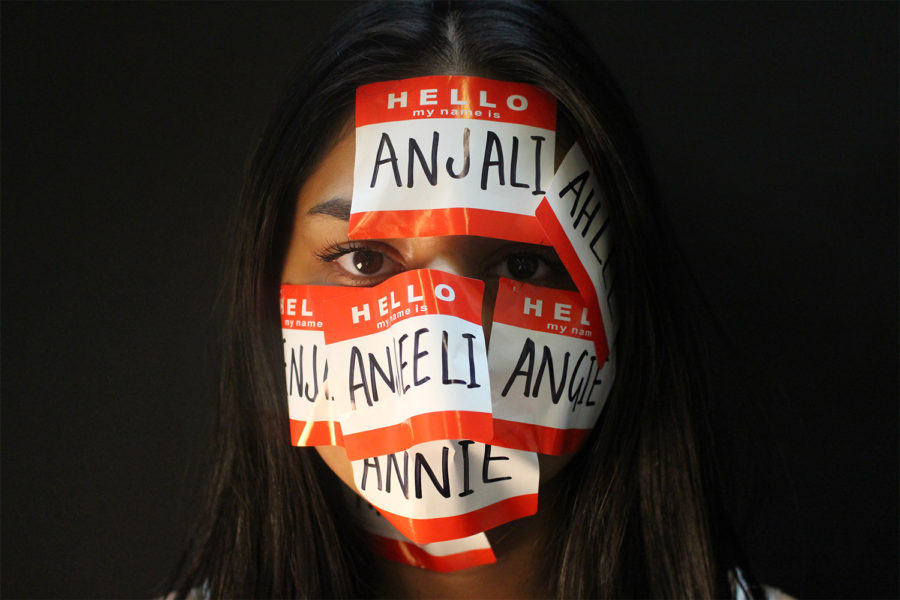

Having one’s name pronounced correctly is incredibly important for some people as names can be representative of one’s culture, heritage, race and overall identity. This makes having one’s name mispronounced a negative and disheartening experience.

Tarika Roy (’21), whose name is of Indian origin, said her name is mispronounced “all the time,” and that when it happens, she feels “frustrated.”

“I kind of dread attendance or dread the first day of school,” she said.

Merriam-Webster defines a microaggression as “a comment or action that subtly and often unconsciously or unintentionally expresses a prejudiced attitude toward a member of a marginalized group (such as a racial minority).”

According to Psychology Today, mispronouncing someone’s name, assigning an unwanted nickname to someone, and making fun of someone’s name are all examples of name-based microaggressions.

Experiences

Ruhan Bhasin (’23) said his name, which is Indian, is mispronounced by both students and teachers “quite a bit.” He said it’s especially common during attendance.

ElSaddic Abd Saddic (’23), whose name is northeast African, said there are “quite a few” ways people mispronounce his name and that it’s “honestly quite unfortunate” when it happens.

“As much as, you know, [my name] can be unique, … when it’s mispronounced, it sort of stings a bit,” Abd Saddic said.

Principal Devan Ganeshananthan said his name, which is of Sri Lankan Tamil origin, has been mispronounced his entire life. In order to combat that, he said he attempts to normalize asking questions about people’s name pronunciations.

“I’ve sometimes actually tried to facilitate that by saying, like, ‘Oh, hi, how are you? How do you say your name?’” he said. “That should lead most, you know, emotionally savvy people to say, ‘Oh, thank you for asking, how do you say your name?’ It’s kind of, you know, showing respect in both ways.”

Social Studies Teacher Shrita Gajendragadkar said her name, which is of Indian origin, is mispronounced “all the time” and in “many different ways.”

“I’ve gotten every version, with all of those letters in it, and also extra letters, and half of the letter missing, and like, for my whole life,” she said.

Gajendragadkar said in order to ensure that her students say her name correctly, every year on the first day of school she explains her name to her classes.

“I spend 10 minutes just going through how to pronounce my name and what it means, and thinking about how names become important to people, and why it’s important to pronounce, or at least try to, pronounce names correctly,” she said.

Gajendragadkar said she found that “students do a much better job than adults.”

This is the first school that I’ve been in where a real great array of people really were interested to know actually how I say my name.

— Devan Ganeshananthan

“I would say probably 99 percent of the time, students have no problem understanding why it matters and taking it seriously,” she said. “Taking on the advantage of learning a new word and how to say it, it becomes almost like a point of pride. Whereas with adults, they avoid it.”

Similarly, Abd Saddic said teachers often mispronounce his name much more than students.

“The younger the kids are, the more they understand, the more they understand to ask first, before trying it,” he said. “With teachers, even with taking attendance, something as simple as that, they do tend to mispronounce it quite a bit.”

However, Ganeshananthan said while he agrees that “kids have a much more open mindset than adults,” he has found that at ASL there is little difference between students and adults in their willingness to pronounce his name correctly.

“The kids here have been absolutely fantastic, really, you know, open, interested, as have faculty and staff,” he said. “This is the first school that I’ve been in where a real great array of people really were interested to know actually how I say my name. In all other schools, it’s been there, it’s kind of been in pockets here and there. But here, I would say it’s pretty, pretty wide, including parents also.”

Effort

Gajendragadkar said while her name is mispronounced “pretty much all the time,” what she takes issue with is when people do not put effort into pronouncing her name.

“It just tends to show they don’t have an interest in actually learning anything about a person,” she said. “I’m not at all kind of like, ‘Oh, you’ve mispronounced it, that’s like a slash on your, your credit’ or something. It’s more, ‘Has there been any attempt? And will they ever ask me how to pronounce it?’ Because I’m happy to help.”

In addition, Gajendragadkar said she places more value on people putting in the effort to say her name correctly than on them actually getting the pronunciation right.

“It’s just about having an open conversation and saying, ‘Oh, how do you pronounce that?’ you know, ‘I want to learn,’” she said. “I think keeping that conversation open is more important than having anyone be correct about it.”

Because of her own experience with her name, Gajendragadkar said she also tries her best to make an effort to pronounce her students’ names correctly.

“It’s an important lesson – if not the most important lesson – to listen to how somebody wants to be called,” she said.

Similarly, Roy said she cares more about whether someone tries to say her name rather than their ability to pronounce it. She said if someone wholeheartedly tries pronouncing her name and fails, it’s “totally fine” and “understandable,” but that she is more bothered by people’s reluctance to learn the pronunciation in the first place.

“It’s only like, the ignorance, or the unwillingness to understand when I do try and correct someone, and the unwillingness to try, when people are like, ‘Oh I’m just gonna call you what I wanna call you’ … That’s where the issue is,” she said. “It’s not necessarily initially mispronouncing it. I understand that part.”

Moreover, Ganeshananthan said he has found that over time, people have become better at putting effort into pronouncing his name and asking about name pronunciations in general.

“It’s increasingly common for people to ask open questions,” he said. “For example, on a Zoom people would say, ‘How do you say your name?’ as opposed to trying to say it on their own.”

In addition, Ganeshananthan said it is always possible to learn to pronounce new names as long as people put in the effort.

“If people can learn how to, you know, pronounce Tchaikovsky, which is a rather challenging name from a Western romance language, people should be able to take the time — and, what does it communicate if people don’t?” he said. “It’s immensely and totally disrespectful.”

Race and culture

Bhasin said he has found a stark contrast between the way people approach his name as opposed to the way they approach more Western sounding names.

“It feels a little weird, because there’s some names that teachers — you can tell they put more effort into trying to pronounce properly,” he said. “Whereas someone like me, who’s like, a person of colour, and Indian, my name gets like, mispronounced, and they don’t bat an eye about it. It also makes me feel like, ‘Does it not matter how my name is pronounced?’”

Gajendragadkar said she has also noticed that people put more effort into learning how to say Western names than they do for names that may be less familiar to them.

“People will go to great lengths to remember and learn and know how to spell names that are familiar to them,” she said. “Given that we are living in the West, the names that are more familiar are European heritage names. There is a pronounced disinterest in learning how to spell and say names from cultures that are not of European heritage.”

Contrastingly, Abd Saddic said, in his experience, race and culture don’t have to do with name mispronunciations. He said since many people don’t come across people with names like his, it is understandable if they mispronounce it.

“I’m from northeast Africa, so it’s not a very common situation to be in. You don’t find many people in ASL from there,” he said. “You can’t blame someone for it. It just depends on your background and who you interact with.”

Roy, however, said her cultural identity plays a significant role in people’s tendency to mispronounce her name.

“I’ve been put into this weird system where like, I’m an outsider in where I am,” she said. “I have a name from a place that’s not the U.S., and it’s not a Western name, so it has a lot to do with my culture that people mispronounce it.”

Furthermore, Ganeshananthan said when people mispronounce his name, or any name in general, it is “absolutely” related to race and culture. He said race and culture play a big role in power dynamics between people.

“Race, power and privilege comes into that an unbelievable, unbelievable, number of times,” he said. “Depending on who is saying it, when they’re saying it, people could have, like, immense power over them.”

Gajendragadkar said she often experiences people being reluctant to say her name correctly due to its cultural origin.

“They just say, ‘Oh, that’s long,’ or they go the other direction and say ‘Oh, that’s so pretty,’ but they never actually try to say, or spell it or call you by it,” she said. “It’s like, ‘Yeah, it’s pretty until you have to have it,’ or ‘It’s pretty until you have to say it, and then it’s just different’ … White culture sees it as different, and therefore not necessary in their world.”

Nicknames

Roy said when people don’t pronounce her name correctly and instead assign her a nickname, it is an “issue.”

“People shorten my name to ‘Tara’ – tons of people have done that,” she said. “No one does that to anyone else. No one does that to an American name.”

Abd Saddic, on the other hand, said he willingly goes by a nickname because it is easier to pronounce than his real name.

“I just give my nickname, which is Elsa, because it’s a lot easier than having to say ElSaddic all the time,” he said. “Some people might say it takes away from my identity, but I’m honestly not too fussed, because I’ve now been known as Elsa.”

Ganeshananthan said he is okay with being referred to as “Mr. G” since he doesn’t want students to feel uncomfortable coming to him if they are unsure of how to say his name. He said if shortening his name “encourages kids to feel more comfortable, that’s totally fine.”

“There’s a little bit of a cost-benefit that I think has to be applied to the situation, mainly because of my position at the school,” he said. “I would not want kids to not have an affinity towards, or comfort, in terms of talking with me if they didn’t know how to pronounce my name.”

I wouldn’t answer to ‘Ms. G’ because I don’t know who that is. I would think that was somebody else.

— Shrita Gajendragadkar

Ganeshananthan also said he has “anglicized” the pronunciation of his first name, Devan.

“That’s not exactly similar to many East Asian families who emigrate to the United States, where they have an East Asian name, and like a, for lack of better explanation, like a Western name, but it is obviously rooted in similar things,” he said.

Gajendragadkar, however, said she chooses to not go by a nickname since she’s never felt she should “hide” her name.

“Your name really can become like a part of who you are,” she said. “I wouldn’t know to answer to something that wasn’t my name. I wouldn’t answer to ‘Ms. G’ because I don’t know who that is. I would think that was somebody else.”

Correcting people

Gajendragadkar said she will tend to correct people when they say her name wrong, but it “depends on the context.”

“If there is an option, like if there’s a moment for me to be able to say my name correctly, then I tend to do that,” she said. “If it’s in like, a big setting, and it is going to be more awkward or more of a problem to interject the correct pronunciation, then I tend not to. I have to sort of weigh, ‘what is the goal?’”

Abd Saddic said while he does correct people when they mispronounce his name, he often feels intimidated to do so when he is correcting an adult as opposed to a peer.

“It’s definitely scary because, especially when it’s with an adult, because you don’t know how to approach the situation,” he said. “If it’s a friend or something, most of the time, they’re understanding and there’s not much to be scared about … But if it’s a teacher, even one you have a strong connection with, it’s especially difficult.”

Ganeshananthan said he acknowledges it can be hard for students in particular to speak up about the pronunciation of their name in front of teachers.

“Let’s say, if I had a student, and I don’t know how to say their name, and I basically give it my best attempt and I don’t let there be any kind of room for conversation about them, I’m sure that then I would be exerting that kind of positional power, privilege,” he said.

Identity and heritage

Gajendragadkar said despite often being teased for her name while growing up, she feels it is an important part of her identity and is something she’s proud of.

“Growing up in a small town in rural West Virginia in America, where my name was very different, there were times where I got made fun of for it,” she said. “It’s that hard thing where it was, kind of, a little bit of a different time period and a different culture. But again, I do feel like I found some pride in my name.”

Gajendragadkar said learning languages such as Latin, Greek, Italian and Sanskrit throughout high school and college helped her appreciate her own name and its history.

“That just made my name that much more exciting, that there were histories associated with it and languages where it did mean something,” she said. “That history, it trumped the, you know, kind of mispronunciations or misidentifications or teasing or mockings because I think, to me, there was just this other bigger history to it, than today, the way that it seemed today in this one particular context.”

Ganeshananthan said his name is “100 percent” a big part of his identity and cultural heritage since it is easily identifiable as a Tamil name. He also said in Tamil culture, people generally only have one name. When his father emigrated to the US, he made his only name his last name, meaning Ganeshananthan’s last name is his father’s name.

“The thing that I really love is like, the uniqueness that comes with my name,” he said. “There’s one of me in the world.”

Catryn • Nov 30, 2023 at 4:38 pm

As someone with a unique first name, I can relate a lot to this article. I do need to set the record straight with Ms. Roy, however. She mentioned that in regards to nicknames, “no one does that to an American name” and that is just not an accurate statement. Below are names of people I know personally who prefer their full length name yet experience their name being shortened all the time.

Danielle to Dani

Jennifer to Jen

Rebecca to Becks or Becky (<– hates that!)

Gregory to Greg

Matthew to Matt

James to Jim or Jamie

Christopher to Chris

I experience that with my name Catryn. People love to shorten it to Cat.

It has been my experience that most people do it out of affection and nothing malice.

Roja • Jan 20, 2022 at 5:01 pm

Great article – check this out :

https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=YRk8XP_PJHk