Today I will debrief the U.K.’s recent decision to increase its nuclear warhead stockpile, the potential reasons as to why this decision was made and the concerns regarding the efficacy of the change in policy.

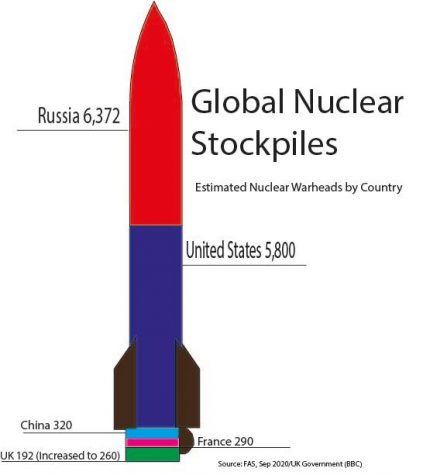

Since the Cold War, the U.K. has been known for its diminutive nuclear status. According to the latest issue of the Economist, the nation’s arsenal is the smallest out of the five other nuclear-armed powers recognized by the Nuclear Non-Proliferation Treaty. In fact, the U.K. has drastically fewer warheads stockpiled than superpowers like Russia, who have around 4,300, China, which has around 320, and the U.S., which has around 3,800 per the Guardian. Whereas, in 2010 the U.K. government stated that the nation had fewer than 225 warheads and planned to further cut down to 180.

Though initially certain that this reduction would be sufficient, the U.K. has pledged to lift the cap on the amount of Trident nuclear warheads it can stockpile by more than 40%. The Economist states that in addition to the increase in warheads from 180 to 260, the government also plans to refrain from publishing any information or statistics regarding the number of missiles and warheads that are to be carried on each submarine, in an attempt to “complicate the calculations of potential aggressors.”

The official reason for this change in policy remains unclear, however, several possibilities as to why this decision was made arise.

An article published by the Wall Street Journal relates the raise in stockpile to Brexit, stating that by exiting the EU, the nation is looking towards strengthening its economy by engraving its place in a more “volatile and fragmented international system.”

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in order for the economy to prosper after Brexit, it must become a power broker with greater control and influence in the Indo-Pacific region, thereby emphasizing the necessity of increasing domestic investment in science and technology.

Furthermore, as mentioned in a landmark post-Brexit review of defence and foreign policy, an argument for an “Indo-Pacific tilt” is posed, in which the U.K. will revise and enhance defence, trade and diplomatic relations with India, Japan, South Korea and Australia in opposition to China.

Another possibility for the increase in stockpile is the government’s growing concern regarding future improvements and developments in Russian and Chinese missile defences. In response, increasing the number of warheads may level out the playing field.

Moreover, a CNBC article states that the Integrated Defense Review, touches on when the U.K. “reserves the right” to use nuclear weapons. The review states that the validity of using nuclear weapons depends on whether other nations used “weapons of mass destruction.” This includes “emerging technologies” such as cyberattacks and more.

However, some were quick to criticize, such as the director at the Royal United Services Institute think tank Tom Plant, who said cyber-attacks should not be included, and that the government lacks understanding of what constitutes emerging technology.

Plant told CNBC that, “cyber is definitely not ‘emerging,’ it’s pretty substantially emerged.” Nonetheless, Plant said he agrees that it is likely for there to be risks surrounding the future future technological advancements, just not through one technology in question – cyber attacks.

Prime Minister Boris Johnson said in order for the economy to prosper after Brexit, it must become a power broker with greater control and influence in the Indo-Pacific region, thereby emphasizing the necessity of increasing domestic investment in science and technology.

With this increase in technology, concerns surrounding the launch of successful chemical, biological, radiological or nuclear attacks in the future have further prompted the increase in stockpile. Although the Guardian mentions little evidence for this assessment, it is clear that the lift in nuclear warheads cap is placed in response to the evolving security environment and the development of technological and doctrinal threats.

However, concerns surrounding the necessity and effectiveness of the lift in regards to COVID-19 have emerged. Kate Hudson, general secretary of the Campaign for Nuclear Disarmament said increasing the production of nuclear weapons would be ignorant and a wasteful use of money: “With the government strapped for cash, we don’t need grandiose, money-wasting spending on weapons of mass destruction.”

Though Hudson poses a valid argument, the U.K.’s lift in the nuclear stockpile is one that historically stands out. It seems unlikely that such a rise would be put in place without pressing circumstances. International threats from superpowers seem to play an integral role in this decision, as a landmark post-Brexit review of defense and foreign policy also included the statement that Russia under Vladimir Putin remains an “active threat” and China a “systemic challenge.”

Though the long term effects of this lift remain unclear, it is nonetheless apparent that the decision was maintained out of precaution and international safety.