Sexual harassment: Shattering the silence

Effects of sexual harassment seep into various facets of life, whether it be through daily interactions, emotional and physical well-being or wider societal culture. Through their own experiences, students and faculty reflect on sexual harassment, the root of the issue, its cyclical manifestation and whom its consequences reach.

May 12, 2021

Traveling alone, for many women, screams danger. Health Teacher Bambi Thompson spent a summer abroad in Madrid for a work opportunity and had the very experience many dread.

“I was on my own and heading down the stairs to go into the metro,” Thompson said. “As I was going down the stairs, a man was coming up. He assaulted me. He put his hands up my skirt and groped me.”

Thompson said her initial reaction was utter outrage. In retrospect, Thompson said she is a “peaceful person that it is slow to anger,” yet when it comes to instances of sexual harassment, she instantly becomes infuriated.

Sexual harassment, the burden most women endure on a day-to-day basis, is one that often remains at the forefront of their minds from the moment they step out their front door to the walk they take to return home each night.

Indecent exposure. Groping at parties. Badgering for sexually explicit photos. Unwanted touching. Rating girls in the hallways. These are only a few of the stories students and faculty shared, while countless others remain untold.

Ninety-seven percent of women aged 18-24 have experienced sexual harassment in public areas in the U.K., according to a survey conducted by UN Women UK. These statistics show that it is a mere 3% away from all women having an experience of sexual harassment.

*Indicates source would only agree to be interviewed with the condition of anonymity.

Defining sexual harassment

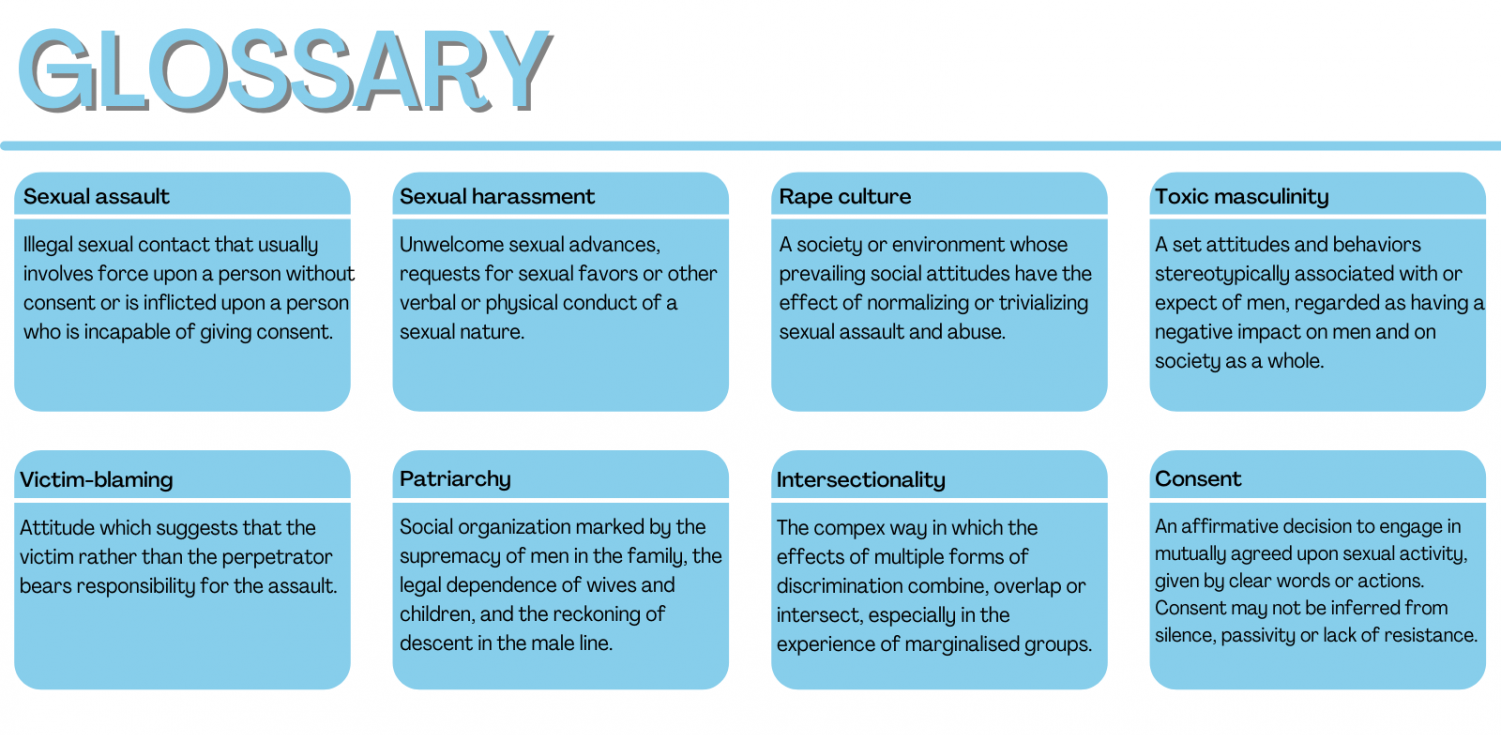

Sexual harassment is “uninvited and unwelcome verbal or physical behavior of a sexual nature, especially by a person in authority toward a subordinate,” per the Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

The United Nations characterizes sexual harassment behavior as “unwelcome sexual advances, requests for sexual favors and other verbal or physical conduct of a sexual nature,” with examples including stalking, sexual innuendos and unwanted sexual looks or gestures.

Eva Eichenberger (’23) said sexual harassment occurs regardless of gender and involves any “attention or behavior that is sexual, unwanted and violating.”

Computer Science Teacher Livia Piloto said sexual harassment is a “spectrum” and an umbrella term for all forms of physical and verbal sexual violence, including assault, abuse and rape.

Gabrielle Yurin (’23) said sexual harassment entails a “lack of consent” and is primarily distinguished by the emotions it evokes as opposed to the action itself.

Source: Merriam-Webster Dictionary and Oxford Languages

Sexual harassment at ASL

Fallon* said the school is far from immune to incidents of sexual harassment.

“Whenever you walk down the hallways, you can kind of always hear a conversation here and there with boys saying, ‘Oh yeah she’s hot,’ ‘She’s such a s**t’ or ‘I would give her like an eight out of 10,’” Fallon said.

Furthermore, Fallon said these unwanted sexual comments, directed towards or about people, constitute an unsafe environment.

“It’s definitely very uncomfortable, especially because it feels like you’re almost watching that girl be violated,” Fallon said. “You feel so powerless because it feels uncomfortable to say anything to them.”

Assistant Principal Natalie Jaworski said sexual harassment is present at ASL because it is a byproduct of the problem on a global scale.

“If we look at any sort of major problem in society, of course those things are going to resonate throughout our little slice of society here,” Jaworski said. “It happens here overtly and covertly every day.”

Ellie Mankarious (’21) said the problem of sexual harassment is amplified and “even more dangerous” on account of the progressive culture often associated with the school community.

“When you believe that you’re so advanced and so progressive and then a problem emerges, you make it into a one-off situation and just think, ‘Oh, no, that’s just that person. It’s not our community,’” Mankarious said. “You’re really just sweeping this massive problem under the rug so that you don’t have to improve yourself and improve your community.”

Fallon recalled that even in the Middle School, sexual harassment was a prevalent issue, specifically with boys participating in sexually explicit games and behaviors.

“I remember they would slap the back of girls’ thighs, which I later learned meant you wanted to sleep with her,” Fallon said. “I also remember that whenever a girl would walk down the hallways, they would stand in pairs or groups of three and discuss if the girl walking by was a top or bottom, which basically meant if she was more sexually attractive on her top or her bottom.”

In order to confront the issue and bring attention to its severity, the school held an assembly in the Middle School where girls shared their experiences. After the assembly, Fallon said discussion surrounding the topic improved because “victims realized that so many other people had gone through the exact same thing and that it wasn’t just them.”

Grade 7 English Teacher Tracy Steege said issues surrounding sexual harassment in the Middle School came to her attention when a student approached her about an incident. She said the student discussed her experience with friends and uncovered the prevalence of sexual harassment, which then spurred the creation of a lunchtime support group in 2017.

Steege said the commonality of boys saying “very sexually explicit things” to girls incentivized the group to organize an assembly to “take their power back.”

“They were so brave and put together this whole thing about sharing and educating that was just incredibly powerful,” Steege said. “I didn’t want to have any voice in that assembly because it was so important that it came from them.”

Moreover, Mairead Doherty (’23) said sexual harassment is “100% a problem in the High School” and is “so bad but nobody ever addresses it.” She said students harass without fear of repercussions.

“In terms of things that happen inside the school, guys talk very sexually literally in front of me and my friends because they think nothing is going to happen,” Doherty said. “They will talk about girls like ‘look at her a**,’ ‘look at her boobs’ and ‘look at her body.’”

Laeticia Perrin (’23) said she remembers an incident last year in which boys engaged in a group chat discussing the physical appearance of girls, which she said ultimately had major implications for the girls involved.

When you believe that you’re so advanced and so progressive and then a problem emerges, you make it into a one-off situation and just think, ‘Oh, no, that’s just that person. It’s not our community.’

— Ellie Mankarious ('21)

“In the moment, one of my friends that had been talked about felt disgusted by herself because of the way they talked about her,” Perrin said. “It’s just incredible the impact they had on girls in our school.”

Max Olsher (’21) said misogynistic and sexist comments are a prominent part of the school culture.

“With my experience of being in places like boys locker rooms or on boys sports teams or spaces that have no women in them, oftentimes talk about women is massively just disgusting,” Olsher said. “Even when there are spaces with women in them, no one is standing up against objectification of women or misogyny.”

Malak Yamani (’23) said sexual harassment among members of the student body not only occurs within the school but extends beyond its walls.

“At a lot of parties, there have been so many incidents where a bunch of vulnerable girls get groped and the boys would then blame it on being drunk or not being in the right state of mind,” Yamani said. “That’s the excuse they use to do what they want to do. Even just around school, the things that you would hear guys say about girls are disgusting. They literally only look at girls for their bodies.”

Doherty said remedying this “violating and shame-inducing” behavior is easier said than done.

“When it really comes down to it, there’s not much you can do,” Doherty said. “Hardly any girls will interfere because they’re scared. They’re not only scared to be talked about themselves, but also it’s high school and people don’t want to be the one to go out in the crowd and say ‘stop talking that way.’”

Mankarious said there is a “tendency at ASL to avoid topics that are controversial,” which she said hinders real progress.

“There are conversations in these clubs, programs and even many classes which aim to target these topics, but then there’s always this line that can’t be crossed,” Mankarious said. “You’re never going to actually deconstruct this system of oppression against women if you don’t cross that line.”

Alec Anderson (’22) said some members of the school community justify its failure to acknowledge the pervasiveness of sexual harassment through comparison to “less progressive” societies.

“People dismiss sexual harassment by saying, ‘Oh, well look at the women in these countries that are facing a lot more inequality than the women in more progressive societies like ASL and London,’ yet it’s so problematic in our community even while subtle,” Anderson said.

Yurin said part of the reason teenage boys neglect the issue of sexual harassment instead of facing it head-on is largely because they do not believe men have a responsibility to bring about change.

“When you say to a teen boy that rape is an issue and that men are harassing girls, they get really defensive about it because they’re not doing it, which is fair enough,” Yurin said. “But also, it’s just important to admit that, you know, while it’s not all men, it’s enough girls to be taking action.”

Olsher also said the school ought to play a major role in supporting students who experience sexual harassment.

“If someone comes to the school saying they’ve been sexually harassed or assaulted by another student, that student needs to face consequences,” Olsher said. “When the school is put into a position of punishing their students for horrible behavior, they need to step up and take that role because students are trusting them with their wellbeing.”

Mankarious said the school should strive for transparency and emphasize that sexual harassment comes with consequences.

“It’s just about being less secretive, more open and making sure people understand that if they sexually harass somebody else, there’s going to be repercussions for that,” Mankarious said. “It’s not just going to be like, ‘Oh, because you have a lot of money, because you’re a senior, because you’re this, because you’re that,’ that you’re going to get away with it.”

Perrin said girls experiencing sexual harassment feel uncomfortable approaching adults within the school about incidents. Reflecting on her own experience with sexual harassment, she deemed the school support system ineffectual.

“I talked about some of my personal issues with the school and they’ve just called my parents when I didn’t ask them to do that,” Perrin said. “My parents were then like, ‘Oh, you’re lying. You just made it up.’ I trusted them, and while I understand they have to do certain things as adults, it just wasn’t helpful.”

Director of Student Support Services and Designated Safeguarding Lead Belinda Nicholson said disclosure of sexual harassment to parents tends to be “very complex” and requires “balancing the needs of the victim with the risk associated to what they’re talking about.”

Consequently, Nicholson said helping students who have been sexually harassed typically involves reaching out to family and guardians.

Jaworski said the school has two primary responsibilities when dealing with sexual harassment incidents.

“As a school, when things happen between students, we need to know that they’re happening, but we also need to think about our obligation as a learning institution to say, ‘Okay, here’s the mistake and here’s how we learn from it,’” Jaworski said.

From a safeguarding perspective, Nicholson said the school has a legal obligation to report incidents of sexual assault to the police. However, she said for incidents of sexual harassment, the administration uses a flowchart that includes a variety of possible allegations to determine the next course of action.

Thus, Nicholson said she encourages students to report incidents to the school or seek help from an alternative source, such as a trusted adult or a helpline. She said students can report incidents by reaching out to any member of the Safeguarding Team, whose names are displayed on posters throughout the school.

Even when there are spaces with women in them, no one is standing up against objectification of women or misogyny.

— Max Olsher ('21)

In addition, following the critical response email sent by Head of School Robin Appleby addressing the rise in sexual harassment incidents across the country, Nicholson said the administration plans to further educate faculty and parents about sexual harassment as well as conduct a school-wide survey to identify potential “holes” in sexual harassment education.

“Part of the work that I’m doing right now is to really go back and do some deliberate education of our faculty about our own implicit bias around gender dynamics, expectations and norms and make sure that we’re creating safe spaces for our kids,” Nicholson said.

Nicholson said working with student groups, such as the Social Justice Council and the Gender Sexuality Alliance, is also imperative to understanding the student perspective and fostering a culture in which community members feel comfortable speaking up.

“Abuse and oppression thrives in silence,” Nicholson said. “There’s no healing when someone suffers in silence. We have a responsibility as a school to take seriously every single allegation and to support our victims.”

Experiences and reactions

Eichenberger said sexual harassment is a frequent occurrence for her to the extent that she “can’t even count the incidents on two hands.”

One time after experiencing sexual harassment, she said that she continued to think about the incident for hours and had “three showers because I felt so invaded and disgusting.”

Jaworski said she can point to such an abundance of sexual harassment experiences that it has become a “normal part” of her life.

“It’s really, really disheartening and actually kind of hard to think about because I have so many to choose from,” she said.

Ruby Read (’23) said incidents of sexual harassment are “horrible” and make her feel “so small in that moment.”

From a male perspective, Anderson said observing the weight of sexual harassment on women in his life is infuriating.

“I get pretty upset because I have three sisters, and I never really thought about how it might affect them,” Anderson said. “I always saw it as something I saw on the news but not really something that affected people close to me. It makes me feel angry because it’s just so hard to feel like I can’t do anything to prevent it.”

Fallon said while her earliest experience with sexual harassment shattered her innocence, it provided insight into the harsh reality of womanhood, and hence it shifted her perception of welfare as a woman.

“It was definitely a pivotal moment in my life because it changed my opinion about my safety and how comfortable I felt within society and in a public environment, especially around grown men as a girl,” Fallon said. “No one had told me this was gonna happen and that this happened to women at all. I had grown up so naively and oblivious to that reality.”

I always ask myself, ‘Why? Why?’ because I wasn’t even wearing a suggestive outfit.

— Colette*

Initially, Fallon said she blamed herself for incidences of sexual harassment. However, she said she eventually changed her mindset to accuse only the perpetrators.

“When I was younger, I would always think, ‘Oh, I did this to myself,’” Fallon said. “But then, as I grew older, I was like, ‘No, this isn’t my fault.’ I can do what I want. I can dress how I want, and I still deserve to not be harassed when I walk outside of my house.”

On the other hand, Colette* said that after her experience of sexual assault by a worker at a London theme park, she continued to question what actions she could have taken that may have resulted in a different outcome.

“I always ask myself, ‘Why? Why?’ because I wasn’t even wearing a suggestive outfit,” Colette said. “Usually, stupid men would ask you, ‘What were you wearing?’ but I was wearing a sweatsuit and I honestly looked like crap.”

In addition, Eichenberger said while she often wants to respond to the perpetrator, the risk of compromising her safety is not worth the sacrifice.

“I’m always just furious that I didn’t do anything,” Eichenberger said. “In the moment, you freeze and you don’t know what to do. There have been so many stories of, you know, women getting aggressive and saying no, and then being murdered or assaulted.”

Colette echoed the notion that instances of sexual harassment spark anger, yet said she feels powerless in those circumstances.

“It makes me so mad when it happens, especially from young ages and also because it’s usually older men – old, white, middle-aged men to be exact – doing the harassing,” Colette said. “It’s frustrating that they know they’re going to get away with it.”

Consequences

Thompson dubbed sexual harassment “dehumanizing” to the point where it exceeds disrespect and is the “opposite of love, equality and fairness.”

Fallon said the dehumanizing aspect of sexual harassment plants a seed in the minds of victims which then grows into larger issues that present numerous challenges.

“Being objectified at such a young age can have such detrimental impacts on you, especially when you’re still developing,” Fallon said. “It could impact your self-esteem, how you think of yourself, your future relationships and it can make you distrust others.”

Laeticia Perrin (’23) said harassment instills distressing emotions and prompts victims to self-blame.

“Boys don’t realize that we’re ashamed of it,” Perrin said. “It makes us feel so bad about ourselves, and we think something is wrong with us instead of questioning men around us.”

Similarly, Colette said sexual harassment experiences stay with the victim, and even when they may feel comfortable enough to come forward, others dismiss their experiences off-hand. For Colette, she said she continually re-lived the moment and criticized her own response.

“There’s also a lot of victim-blaming,” Colette said. “People often just say, ‘Well, it’s your fault’ and ‘You let that happen to you.’ Especially after my really bad experience, thoughts kept running through my head about what I would have done, but when it happens to you in the moment you’re really just shocked and don’t know what to do.”

Fallon said the common reactions to those coming forward with their experiences are disappointing and deter other women from sharing their stories.

“It is just so sad to see all of these girls go through these things and then just be utterly dismissed and not cared about, like they are literal trash and that everything will be forgotten in like two or three days,” Fallon said.

On the other hand, Thompson acknowledged that one of the perversities around sexual harassment is that those who belong to the 3% of women in the U.K. that have not yet experienced harassment may question their value and feel unworthy in the male gaze.

“They might think, ‘What’s wrong with me if I’m not getting sexually harassed?’ and ‘Am I not attractive enough?’” Thompson said. “It’s so twisted, but it just reflects the society we live in. You really can’t win.”

Moreover, Olsher said women and people from other oppressed communities, such as members of the LGBTQ+ community and people of color, suffer the impact of sexual harassment on a much greater scale.

Boys don’t realize that we’re ashamed of it. It makes us feel so bad about ourselves, and we think something is wrong with us instead of questioning men around us.

— Laeticia Perrin ('23)

“From what I understand as someone who comes from marginalized communities, there’s a difference between when an oppressed group punches back at an oppressive group than when an oppressive group punches an oppressed group,” Olsher said.

Yurin said the prominence of sexual harassment pushes safety to the forefront of women’s minds to the point where girls “think about it and deal with it on an everyday basis when we’re out alone.”

Ultimately, Fallon said sexual harassment is an issue entrenched in our society and an unacceptable yet painful reality for most women across the globe.

“No one should have to be scared to walk outside of their house in fear of getting harassed on the street,” Fallon said. “No one should feel extremely unsafe when they leave their house – period. Like, who knows? Are they going to follow you home? Are they going to assault you? Are they going to kill you? No one should have to deal with that ever, let alone on a daily basis.”

Intersectionality

Intersectionality is the “complex, cumulative way in which the effects of multiple forms of discrimination combine, overlap or intersect especially in the experiences of marginalized individuals or groups” according to the Merriam-Webster Dictionary.

Thompson said gender, sexuality, race and socioeconomic class are all factors that influence which cases of sexual harassment gain attention from the media and the general public.

For example, Thompson said two women of color, Nicole Smallman and Bibaa Henry, were killed in a London park this summer, yet very few were aware of the incident. She said this event lies in stark contrast with the response to the kidnap and murder of Sarah Everard, who was a white woman. Although she said the two incidents were similar, the media only popularized the Sarah Everard case.

“You didn’t see it in the media, probably because they were two women of color,” Thompson said. “There’s a lot of harassment of women, but if you think about race or other marginalized groups, like transgender or members of the LGBTQ+ community, it can also be a hate crime.”

Olsher concurs that sexual harassment poses a risk to marginalized groups, as they said receiving equal attention and care for instances is a prevalent issue.

“The picture of a sexual harassment or assault victim or survivor tends to be a white woman,” Olsher said. “It’s 100% fantastic that white women are feeling empowered and able to call out their assaulters and harassers and are reclaiming that power and holding people accountable for their actions. However, it’s then 10 times harder for those that are not white women.”

This awful tangle of systemic oppression, racism, stereotypes and the sexualization of women of color is still very much intact and it involves absolutely everyone, not just minority groups.

— Ruby Read ('23)

Read said that as a woman of color, the intersectionality of race and sexual harassment “hits close to home,” and is a consequence of entrenched racism in society. She said racism unjustly shifts blame from the harasser to the victim on the basis of race or other identifiers.

“People within marginalized communities are being blamed for sexual harassment just because of the way they look or stereotypes of the way they act,” Read said. “This awful tangle of systemic oppression, racism, stereotypes and the sexualization of women of color is still very much intact and it involves absolutely everyone, not just minority groups.”

Moreover, Olsher said this widely accepted perception of a female victim has implications on male victims coming forward with their experiences.

“When you have a male that comes forward to talk about it, oftentimes you’re hit with things like, ‘You should have enjoyed it,’ or ‘You’re so lucky this happened to you,’” Olsher said. “It’s like people believe that it happened, but they don’t believe how it happened. They believe you perceived it wrong.”

Confronting the patriarchy

Olsher said the patriarchy is undoubtedly responsible for harassment incidents against women as well as reflects the “staggeringly high amount of people who have experienced it.”

“The disgusting statistics we see with the frequency of sexual assault attacks is an archaic leftover branch of intense patriarchy and of a time where no woman was considered a living, breathing creature,” Olsher said.

Eichenberger said it is a “no-brainer” that we are living in a patriarchal society, which she said is a tremendous contributor to the normalization of sexual harassment.

“It’s a taught behavior, and men feel like it’s okay because they’ve never been taught that women aren’t objects,” Eichenberger said. “That’s the fault of parenting, the education system and the people that they associate themselves with.”

Mankarious said she is disgusted the patriarchy persists and has not yet been dismantled.

“At this point in history, I’m just so done with it,” Mankarious said. “Just get over it already. Act like a responsible human being and don’t harm other people. There have been so many times when I’ve been harassed and I just think to myself, ‘Do you not have a mother?’ ‘Do you not have a woman in your life that you respect?’”

Eichenberger said toxic masculinity is another component to the origin of sexual harassment.

“Part of the patriarchy is that men don’t feel like they can be vulnerable and they don’t feel like they can be emotional, so there is a lot of pent-up anger,” Eichenberger said. “Men need to physically overpower someone to make themselves feel good, which results in violence against women and really festers in our society.”

The disgusting statistics we see with the frequency of sexual assault attacks is an archaic leftover branch of intense patriarchy and of a time where no woman was considered a living, breathing creature.

— Max Olsher ('21)

Similarly, Mankarious said many boys are reluctant to admit their wrongdoings and actively work to resolve the issue because they do not want to be perceived as inferior.

“Sometimes there’s this really toxic environment where boys think that if other boys care about these issues, then they are emasculated in some way,” Mankarious said. “That is just so ridiculous to me because I have so much more respect for people that are willing to come out and say, ‘Yeah, I have made these mistakes. I do actually have these problems.’ Yet, it’s much easier for boys to just say, ‘Oh, that’s not me. That’s everybody else.’”

Olsher said the resulting societal culture is a principal contributor to the persistence of sexual harassment.

“It stems from this idea of male invincibility and this idea of ‘locker room talk’ and how it’s acceptable to talk down and talk horribly about women, about their bodies, about what you want to do to their bodies,” Olsher said.

Jaworski said sexual harassment is a man’s way of exerting power over women.

“I don’t necessarily think that men expect that they’re going to get a date with that kind of behavior,” Jaworski said. “It’s about the fact that they’re able to minimize women and view them as objects and therefore have power over them.”

Doherty said misogyny and patriarchal tendencies are a “spiral that never ends,” and as a consequence, men feel entitled to women.

“It comes down to men just feeling like they deserve something when they absolutely do not,” Doherty said. “They don’t even understand when no means no. It is also the way our society is built and how boys are raised to think that they are deserving of a ‘piece of a**’ whenever they want it.”

In addition, Yamani said boys “don’t really want to take no for an answer,” and when they receive that response, it “makes them want it even more.”

Yurin said sexual harassment endures due to the fact that all members of society are not yet aligned with modern-day expectations and social justice headway over the decades.

“For a long time, as in human history, it was considered that women were the vulnerable ones, the ones that are, you know, set out to fulfill [men’s] sexual desires,” Yurin said.

Anderson said sexual harassment is a “form of inequality” and comes down to the “basic understanding that everyone is created equal.”

“It’s not okay to think that you’re better than someone else because of the sex that you are born as,” Anderson said.

Ultimately, Colette said despite social progress, misogynistic ideas and sexist treatment of women still play a key role in the tenacity of sexual harassment.

Combatting complicity

Yurin said the normality of sexual harassment is detrimental and remarkably frustrating because it is “such a mundane thing now.”

Thus, Eichenberger said many “don’t even give it a second glance when it happens.”

“It’s so normalized that I’m not even the slightest bit surprised when every single one of my friends has been sexually harassed,” Eichenberger said.

Eichenberger said even though bystanders may want to speak up, being with their friends acts as a deterrent from expressing their disapproval aloud and, therefore, causes them to ignore the situation out of fear that it would be “embarrassing.”

Furthermore, Doherty said women feel compelled to conform to expectations set out by society that promote a culture of victim-blaming.

“There’s still a stigma that it’s the fault of the woman,” Doherty said. “People will always say ‘don’t wear skirts that are too short,’ ‘don’t be flirty,’ ‘don’t be too nice,’ but ‘don’t be too moody either.”

Similarly, Yamani said girls are expected to bear the responsibility of preventing sexual harassment.

“It’s always been like, ‘Girls, you should cover up so that guys don’t look at you,’ ‘Girls, you should be careful what you wear,’ ‘Girls, be careful what you say’ and ‘Girls, be careful how you act,’” Yamani said. “Women are not just a piece of object that men can do whatever they want to, so treat them as equals.”

Olsher said accountability is lacking when seeking justice for victims of sexual harassment.

“On the reaction side of things, assaulters and harassers are not held nearly as accountable as they should be,” Olsher said. “The criminal justice system is not geared towards giving survivors justice.”

On the other hand, Olsher said a lack of understanding about consent shows “a massive rift in society, where men are socialized and taught that they can live without consequences and that the bodies of other people around them, especially women, are at their expenditure.”

Even so, Fallon said the world is headed in the right direction, with movements and organizations such as #MeToo, Freedom from Violence and The New York Women’s Foundation gaining traction.

“Lately, these movements for women’s rights have definitely helped a lot to break down the barriers and start conversations between people about these difficult topics,” Fallon said.

Another movement surrounding sexual violence has recently emerged through a platform called “Everyone’s Invited,” with an Instagram counterpart. The platform has garnered over 16,000 anonymous testimonies from students across the U.K. as of May 12.

Stories posted on the platform range from accounts of sexual attacks to verbal harassment to unwanted touching, all shedding light on the rape culture and victim-blaming of schools across the country.

One account shared on “Everyone’s Invited” came from someone who identified themselves as a former ASL student, with her own testimony to a criminal sexual attack in the back of a taxi.

Next steps

Fallon said the first step in combatting sexual harassment is creating an environment in which all members feel comfortable engaging in open conversation.

“Having conversations about, first of all, what men can do to help women feel safer and also helping educate people who haven’t necessarily gone through these experiences about what it is, what they can do to help and what needs to happen to change this issue,” Fallon said.

Jaworski said forging a partnership between men and women as well as having discussions with men is crucial to combatting sexual harassment.

“One of the most important things is to make sure we are engaging boys and men in this conversation and saying that we’re partners in this together,” Jaworski said. “A lot of the negativity and toxic masculinity actually breeds in spaces where women aren’t, so that’s why men have to be empowered to call each other out when they make sexist remarks.”

One of the most important things is to make sure we are engaging boys and men in this conversation and saying that we’re partners in this together.

— Assistant Principal Natalie Jaworski

In addition, Eichenberger said encouraging victims to seek help and report cases of sexual harassment is imperative.

“With the police system and the justice system, we need to start taking this issue seriously and it needs to be normalized to report sexual harassment and assault,” Eichenberger said. “We need to stop frowning upon it.”

Fallon said that regardless of gender or background, it is crucial to “believe the victim because disregarding them is just bringing on a whole new level of shame and guilt for all women.”

Anderson said despite the type of sexual harassment, it is crucial to listen to the experiences of women and “take them seriously.”

“It’s really important to recognize that almost every single woman has gone through something like this,” Anderson said. “If boys just keep making jokes about it, the problem is just going to get worse.”

Moreover, Yurin said “attacking the root and not the symptom” is critical when tackling sexual harassment.

Thus, Colette said educating younger generations should be a priority.

“The only way we can fix this issue is just to keep the younger generations informed and ourselves informed because we are the future,” Colette said.

Ultimately, Thompson said tangible change is stirring among younger generations, and that we should continue to foster a “culture of accountability.”

“Your generation gives me so much hope because young people are saying, ‘It’s not okay’ and ‘It’s not enough,’” Thompson said. “Between social media and social justice, I see this real movement. There’s a very real, very clear desire by a growing number of young people to make a substantive change, and it is so encouraging.”