Community members share eating disorder struggles

Raised by a single father in the Marine Corps, SLD Department Head Heather Statz said she grew up in an environment where voicing one’s negative emotions was uncommon, causing her to bottle up her feelings.

“Unless it was positive and happy, I pushed it down,” Statz said. “For me, that manifested itself in an eating disorder.”

However, Statz said her eating disorder was attributed to various influences throughout her childhood, later becoming a multifaceted issue that spanned 26 years.

“When I felt things were spinning so out of control, when I felt I had no control over my life, [eating] was something I could control,” Statz said.

ED glossary by vittoria_di_meo

Abrial* requested to remain anonymous due to privacy concerns.

The Oxford English Dictionary defines an eating disorder as any mental condition that causes a disturbance to eating behaviors and negatively impacts one’s physical and psychological health.

Abrial* said she struggles with anorexia and body dysmorphia, triggering a constant internal battle.

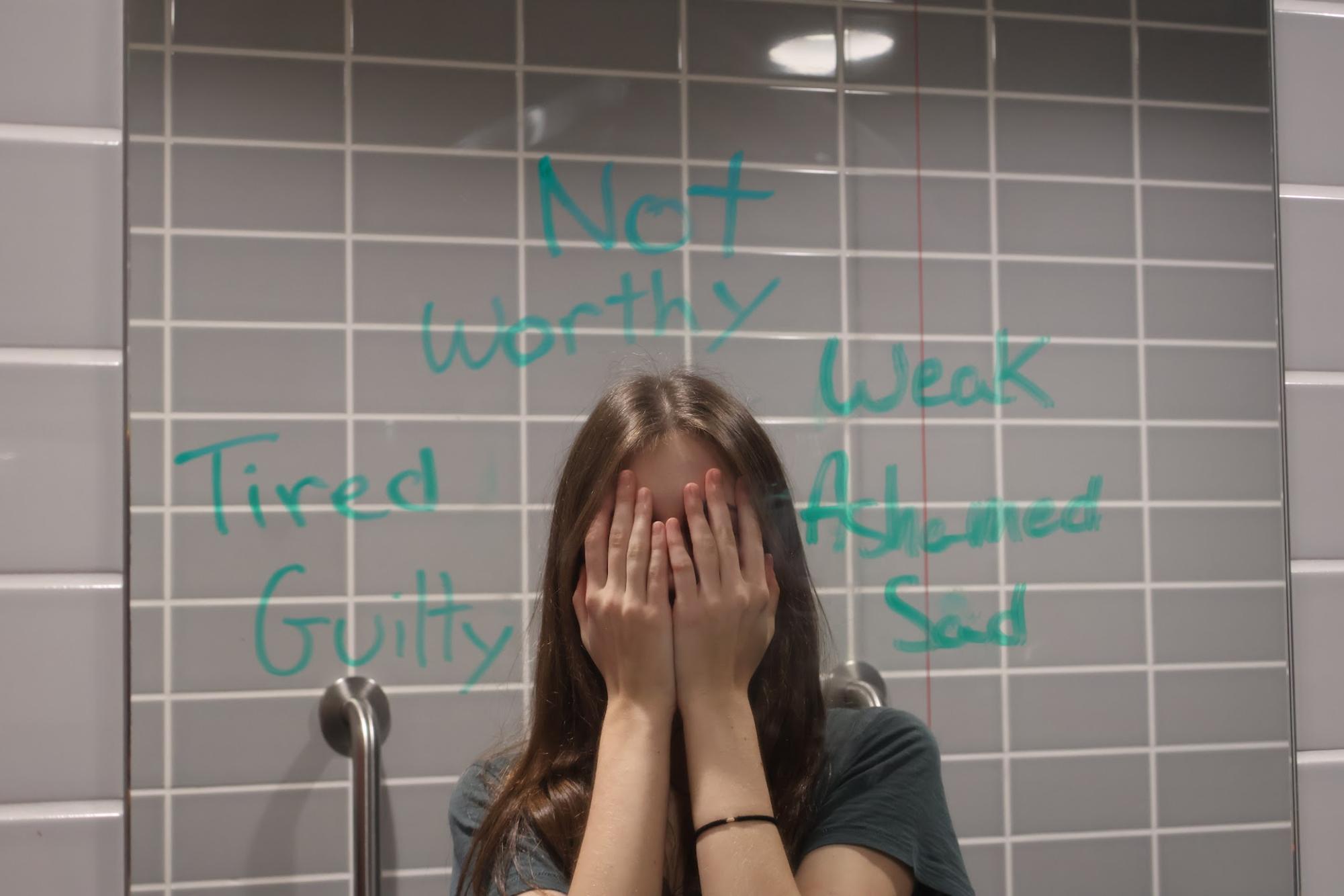

“I often look at myself in a mirror and think that I’m not skinny enough or that I am not worthy enough,” Abrial said. “I feel like I don’t have control over my body and my mind and sometimes that leads me to not eat anything.”

According to Eating Disorder Hope, 2.7% of teens will experience an eating disorder in their lifetime and 13% of young adults will develop a disorder by the age of 20.

Math Department Head David Hill said he has been confronting emotional eating for most of his life. Hill was raised by a full-time working mother, and his two older brothers lacked an understanding of proper serving sizes.

“No one was at home telling me what to eat and about portions,” Hill said. “I didn’t learn about that until really after college, and I realized that I have to be conscious about what I’m eating.”

Furthermore, Hill said he simultaneously suffered from depression, exacerbating his eating disorder and tendency to revert to old, unhealthy habits.

“Another factor for me is that it’s harder to control my eating when I’m tired and I don’t have time to plan and cook,” Hill said. “So when I’ve had a long day at work and I don’t have food at home, it’s really easy to just Deliveroo and order something.”

Alternatively, Abrial said her eating disorder began at the realization that she didn’t fit into her ideal body type.

“It is still something that I struggle with on a daily basis,” Abrial said. “You feel all of those emotions constantly cloud your brain and they also completely consume you as a person.”

Statz said she began naturally losing weight at the age of 17 and soon began receiving compliments for her bodily changes.

“I wish I could say that it didn’t matter, but it really mattered at that time,” Statz said. “I wanted to keep it, so I perpetuated that weight loss that was happening naturally. I wanted it more.”

Additionally, Statz said her eating disorder served as a tool to avoid confronting negative emotions, as she lacked the experience to have healthier judgment.

“[Anorexia] was helping me not to have to deal with certain things until I was at a place where I could,” Statz said. “There was no part of me that was playing all of this out and had the hindsight and the wisdom to be making conscious decisions.”

Abrial said comparing herself to professional athletes in her sport dramatically affects her self-perception.

“I compare my height, my weight, my size,” Abrial said. “That can definitely bring me down and make me go back into a hatred toward myself and a self-harming mindset.”

Moreover, Abrial said seeing athletes around her battling with similar disorders caused these issues to become a mutual experience in her sport’s community. Soon, an unspoken precept developed between her and her fellow athletes.

“We would have those silent agreements to not eat with lots of people and to find little escapes from food,” Abrial said. “You’re in it together and you’re both starving yourselves, almost like you have a community to do that with, with the most unhealthy friendships in the world.”

On the other hand, Statz filled her schedule in a manner that could be perceived as healthy with activities like exercise to minimize others’ concern about her eating patterns.

“When you fill your schedule with going to the gym, no one can tell you it isn’t a great thing,” Statz said. “But I don’t think people realize I was also doing that to the extreme.”

Moreover, Statz said she would constantly keep track of her exact calorie count and avoid going out to eat with friends to avoid social situations requiring her to eat in public.

“For 26 years, there was not a single day or moment of the day I couldn’t tell you how many exact calories I had,” Statz said.

Hill said his recovery journey fluctuated, including times where he formed healthy habits before experiencing periods of regression.

“I followed a lot of the bad advice that you get when you follow the bad trends,” Hill said. “Those intense workouts and diets that are not sustainable, and I did a lot of that for like six to eight years.”

Similarly, Statz said self-induced academic pressure drove her eating disorder to a grave degree.

“In college, I ended up in hospital during finals because I wanted to have straight As,” Statz said. “I did not want anything less. I was not nourishing my body. I was absolutely having the hunger fuel me and make me feel powerful.”

As an athlete, Abrial said her ongoing participation in her sport caused physical and mental exhaustion due to her unchanged eating patterns.

“You’re battling hunger, and feeding yourself is a human necessity, but also you can’t because in your mind you’re not worthy of food,” Abrial said.

This student now recognizes that this was an unhealthy way to think about food and they have since gotten help.

Abrial said strong sentiments of guilt were a large component to her disorder, beyond the physical exhaustion.

You feel all of those emotions constantly cloud your brain and they also completely consume you as a person,” Abrial said. “And it’s so exhausting, you are so f***ing hungry all the time.”

Moreover, Statz said her restricted diet had numerous severe physical implications.

“My body was basically poisoning itself because [it was] trying to grab nutrients from [my] organs and in places that it shouldn’t be because I wasn’t giving it what it needs,” Statz said.

In addition, Statz said disruptive dietary patterns further infiltrated the social aspects of her life, as she frequently missed events with friends in an attempt to conceal her eating habits and avoid confrontation.

In addition to the physical challenges his disordered eating caused, Hill said judgment from others, including professionals, is a constant battle, ultimately hindering his motivation for his recovery journey.

“For somebody who doesn’t know my journey and just sees that I’m overweight, they may catch me eating bad one day and they’ll judge me,” Hill said. “I just wish people would acknowledge that they don’t know what journey you are on, and if you actually want to help me, you should figure out where I’ve been.”

Likewise, Statz said she felt judgment concerning her eating disorder and a sense of external discomfort when voicing her dietary struggles to others.

“There seems to be shame around it,” Statz said. “Without realizing I think people would be like, ‘Well, that’s silly, why would someone do that?’ or something, but it’s more complex than that.”

Additionally, the manner in which the media portrays unrealistic body standards has contributed to Statz’s eating disorder.

Echoing Statz, Abrial said the media generates untrue realities and stereotypes of the struggles of an eating disorder.

“I don’t think anyone chooses to have an eating disorder, which is something that the media perpetuates, that you can choose this lifestyle of not eating,” Abrial said.

Furthermore, Abrial said social media can glamorize the reality of dietary disorders, shining an illusive positive light on harmful conditions and portraying such eating habits as beneficial.

“They often get talked about as a life hack or a tip to a healthier lifestyle, when it’s not actually healthier, it’s way more dangerous,” Abrial said.

Hill said he would reassure others struggling from an eating disorder and encourage them to seek the necessary help.

“An eating disorder is just like any other disorder, there’s nothing wrong with you,” Hill said. “If people try to make you feel bad, they don’t want to see you get better. Sometimes there are professionals who are like that and that’s the reality of our world … That may happen but don’t give up.”

Hill said he was initially reluctant to admit to his eating disorder, facing progress fluctuations during his weight loss journey.

“I don’t think I used the language ‘eating disorder’ until probably three or four years ago when I started researching bariatric wards and started seeing research about how eating disorders lead to obesity,” Hill said. “I would say I’ve been on a weight loss journey that I’ve been trying to take seriously for the past 12 years and it’s been up and down.”

Similarly, Abrial said she refused to acknowledge her disordered eating and avoided the problem.

“Self-denial for me is huge,” Abrial said. “I would just say it’s a subconscious mind game with yourself. Even now that I know, I still somewhat deny it.”

High School Counselor Yanna Jackson said if a student thinks a friend might be exhibiting symptoms of an eating disorder, they should try and talk to their friends and eventually a trusted adult.

“With friends, there’s a relationship there already and I think it’s okay to tell people that you might be worried about them,” Jackson said. “Also say that you’re not coming from a place of judgment, and if a student is seriously worried about their friend, that’s the case where you could call a trusted adult.”

Statz said the birth of her daughter pushed her to confront her struggles with an eating disorder. In order for her daughter to grow to her fullest potential, Statz said she needed to be a role model for her child.

“Looking at [my daughter], I wanted to be honest for the first time about what is really going on with me,” Statz said. “I have disordered eating, but I am stronger than those behaviors and through intention and mindfulness and being fully present I can combat the unhealthy behaviors.”

Moreover, Statz said after recovery with external support, she has learned to quiet the voices inside her head that push her back to her disordered tendencies.

“I eat when I’m hungry, I’m not overanalyzing it,” Statz said. “I’m not counting every single calorie, I’m trying to eat from inside food groups again. Having a child, like, I want to be a good role model of nutrition.”

“Looking at [my daughter], I wanted to be honest for the first time about what is really going on with me. I have disordered eating, but I am stronger than those behaviors and through intention and mindfulness and being fully present I can combat the unhealthy behaviors.”

— SLD Department Head Heather Statz

High School Counselor Johnice Moore said students looking for support are always welcome in the counseling office.

“There’s people out here to support you and walk you through the stages to get to where you need to be,” Moore said. “There’s always support,”

In addition, Jackson said students may be referred to outside experts.

“Coming to the counseling office is a great resource, but sometimes it’s beyond our practice in school,” Jackson said. “If someone wants to talk about it outside of school, we can provide a referral to an outside therapist or a trained specialist.”

Hill said the most important step in his journey to recovery was seeking professional help. Still, when doing this, he experienced both ups and downs in his journey, from dealing with other people’s prejudice to learning about healthy alternatives to curb unhealthy habits.

Echoing Hill, Abrial said despite the coping strategies she was able to learn, therapy brought about fluctuations in her recovery journey.

“You start with therapy to change your thinking around food,” Abrial said. “With that, some days it feels really good, you feel like you’re getting somewhere, and some days you don’t.”

Furthermore, Abrial said she talked to friends and coaches to help hold her responsible for her eating patterns, ensuring a steady path to recovery.

“I can count on them to make sure I’m eating and if they notice that I’m not, to hold me accountable,” Abrial said. “If you can acknowledge it yourself, even for a short period, long enough to tell someone, then they can make that hard decision for you, they can guide you on the right path.”

Ultimately, Statz said talking to counselors and her colleagues helped her come to terms with her eating disorder, despite its emotional difficulty.

“I was finally able to say it, and after I took away that shame then I could actually start working on this disorder,” Statz said. “My eating disorder doesn’t totally define me, but it is still a part of me and my journey, and I’m not ashamed.”