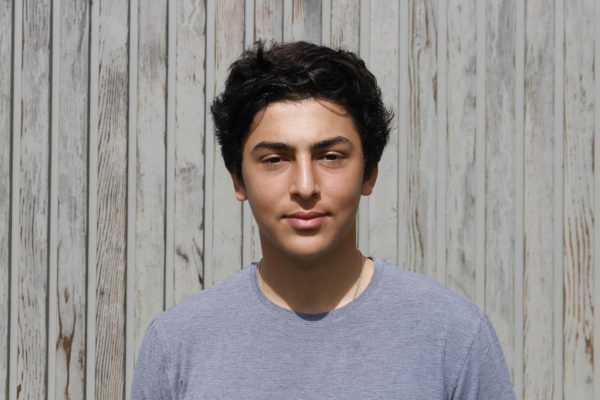

When Daniel Olshanskiy (’25) started training for soccer academy Oxford United in Grade 10, he recalls traveling over an hour to Oxford from school four times a week for training. On Saturdays, he would travel further for games in places such as Bristol and Manchester. Olshanskiy said he spent a lot of time commuting, resulting in fewer hours to study.

For many budding players like Olshanskiy, the process of becoming a professional soccer player often starts at the academy level. Professional teams develop players through their academies comprised of youth teams until they make it into the professional team or are released, according to Junior Grassroots Football UK.

Academies train at the club’s training ground often in the suburbs and far from cities where their players live. Traveling, gym work, and football training are part of the commitment. At the end of each year, clubs decide which academy players have enough potential to be moved up.

Sam Keller (’27), a goalkeeper for Watford, said after a full school day, he travels an hour to get to training. Practice ends at 7 p.m., and he travels for another hour to get home before he does his homework. Keller said this leaves him barely any time to spend with his friends.

“Playing for an academy really limits your social life because if you don’t invest all of your time into soccer, someone else will take your spot,” Keller said.

Moreover, Keller said academies aren’t worried about their players doing well in school.

“Once a week, after training, coaches will give you an hour that you can use to do school work which you are missing out on,” Keller said. “Other than that, they don’t offer much help for your schoolwork.”

On the other hand, Emerson Beatty (’25), an outfielder for Watford, said coaches are understanding when balancing training and other commitments on occasion.

“We’re lucky that we have a big squad because we can miss a game once in a while but still have players to fill our spot when we’re gone,” Beatty said. “Coaches don’t get mad if you miss an occasional training or game.”

Moreover, Beatty said even though soccer has not had a major impact on her daily life, balancing all of her commitments requires good time management skills.

“I don’t think [academy soccer] affects my life too much, other than not being able to spend as much time on schoolwork,” Beatty said.

Additionally, Olshanskiy said there is pressure to succeed academically in case a career in soccer doesn’t work out, although it is challenging to juggle both.

“If you get released at 18, you have already completed the school that they provide for you which is very limiting for your GCSEs which means you have very little school credit,” Olshanskiy said. “[It] leaves you with not being at the club and not having the credentials to get a good job.”

Beatty said although academy soccer is a competitive environment that leaves not much time for academics and social events, she still finds it rewarding.

“A common misconception is that academies are all serious and strict,” Beatty said. “But we also have a lot of fun while training.”