Religion and Curriculum

Social Studies Department Head Natalie Jaworski stands in front of her World Civilizations I class, where she is teaching about the world religions, beginning with the philosophies and belief systems of the Axial Age and transitioning to the Abrahamic faiths.

Jaworski believes that by studying religion through two lenses, a faith lense– what it means to believe in the religion– and a historical lense of data and verifiable information, empathy for every religion is created. These lenses allow students to study each religion without cultural constraints. “The purpose of studying [religion] is to say that regardless of what can be proven historically, to be a believer is to have faith,” Jaworski said.

When studying religion in a classroom, Jaworski strives “to create a safe space to talk about different faiths” in a way that helps students understand why people of different religions believe in their faith. “There is a way to think about and question faith without being aggressive or abrasive,” Jaworski said.

Although Ally Negasheva (’17) does not believe in a God, she feels that the teachers at ASL, specifically Social Studies Teacher Todd Pavel and English Teacher Peggy Elhadj, (who taught Negasheva AP European History and Russian Literature) have helped influence and form her opinion on religion through multiple conversations about the subject. Negasheva believes that they have made her look at religion with very different perspectives. “Listening to [them] talking about it makes it sound more euphoric and I really appreciated them doing that for me,” she said.

Elhadj, who also teaches Middle Eastern Literature, chooses texts for her classes based on their “handling of the topic” of faith and she would not choose a text “which was inherently critical of a [specific] religion.” She appreciates that the students in her class continually share in a vulnerable way, which allows everyone to learn “from a basis of ground zero.”

At the beginning of every semester, Elhadj asserts that she has no bias pertaining to a specific race, religion or last name. “I try to make it clear at the very beginning that I’m a Christian from Boston, I married an Arab, my best friend is Jewish, I went to a Jewish college, I’ve lived in Saudi Arabia and I don’t really have a bias,” Elhadj said. “I want every student to feel comfortable expressing his or her concern.”

Contrary to Negasheva’s beliefs that the school discusses and teaches a diverse range of religions, Bader Al Hadlaq (’18) doesn’t believe the curriculum helps to create an atmosphere of religious acceptance. Often times, Al Hadlaq feels that “the school most definitely doesn’t care” to teach students about respecting other religions or different perspectives.

In class discussions, there have been instances when Al Hadlaq felt that his voice is not heard when it comes to discussing religion and religious conflicts such as the Charlie Hebdo attack in Paris and violence in the Middle East, often being the only Middle Eastern student in his class. “It makes me feel disregarded, it makes me feel like [my opinion] is unimportant [in] people’s eyes,” Al Hadlaq said.

Al Hadlaq further believes that institutionally, ASL doesn’t fully represent everyone’s religious backgrounds and differences. “[The school] should respect everyone’s values, not the majority’s. There’s a difference,” Al Hadlaq said.

Stereotypes and Freedom of Expression

Jaworski believes in general the school environment is safe for teachers to express their religions openly. “I think teachers feel comfortable doing that if they want to, but in the same way as teachers might not want to express their political view, faith is personal,” Jaworski said. “Some teachers might want to talk about it and use their personal experiences in a way to teach, where other teachers might not.”

Contrarily, as a student, Al Hadlaq doesn’t feel comfortable expressing his religion at ASL. This is mainly due to the attitude that he believes is present of some people not wanting to talk to a person because of their religion and race. “I don’t express my religion because the fear of people judging me the next time I speak to them,” he said.

Al Hadlaq believes this is also largely attributed to religious stereotypes and the rise of Islamophobia. “I think it’s more apparent in today’s culture that you can say whatever you want and there’s no restrictions just because there is so called freedom of speech. There is of course restrictions, but nobody knows that,” he said. “People think that they can say whatever they want without any impact or conflict.”

Similarly, Carter* (’18) doesn’t believe that the environment at ASL is one where he can openly share his religion, Islam. “I don’t think I’ve ever really found that I’ve been able to express my faith,” he said. “People don’t necessarily have full awareness and knowledge of the religion to fully understand.”

Carter further believes that this lack of knowledge results in the prevalence of stereotypes. “People have these set images of what one is supposed to be based on their religion,” Carter said.

Aside from stereotypes, Carter believes the disagreements that arise when talking about religion prevent him from fully expressing his religion. In a school trip, Carter experienced conflict between his religious beliefs with another’s when “someone was saying ‘there’s no God, we’re all going to hell anyway’,” Carter said. “I have seen people when talking about religion get very emotional and invested in it. The topic [of religion] is one that can divide people quite easily.”

Despite the religious stereotypes that some believe are present, Thalia Bonas (’20) doesn’t think that students at ASL have preconceived notions of certain religions. Bonas credits how “ASL is so diverse as a school [and] everyone is comfortable with each other,” to her ability to freely express her religion. “I don’t think ASL has a bias more than anywhere else.”

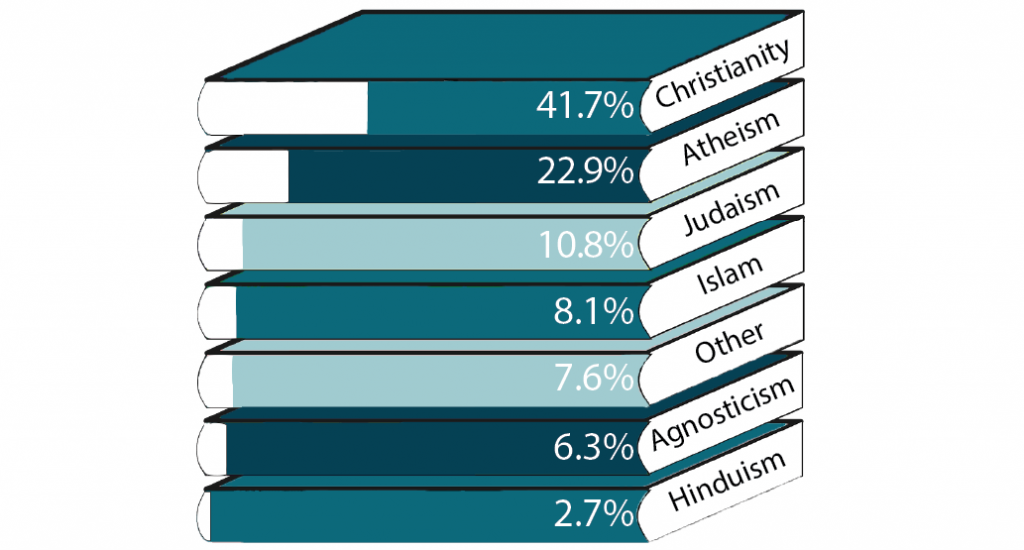

Bonas recognizes that the Jewish traditions she celebreates are not widely represented in the community, unlike Christian celebrations, which are focused on more. However, she believes that it is normal considering the religious demographic of the student body with Christianity being the dominant religion.

However, Jacob Nathan (’19) agrees with Al Hadlaq and believes that religious stereotypes are still evident in the community. During a heated conversation with another student, a religious slur was used and the other student said, “You’re not paying me because you’re Jewish.” Because of this, Nathan feels as if the stereotype of Jewish people being pinned as “liars, stealers… hoarding money and controlling banks,” are still present. “I don’t think those stereotypes have disappeared, I think they are less prominent,” he said.

These stereotypes are recognized by Jaworski, and by studying religion, she believes that the stereotypes can be reduced. “Our job, particularly in World Civilizations, is to break down those stereotypes…to make sure that we are showing that there is not a stereotypical way to think about a certain religion,” she said.

By deconstructing stereotypes, Jaworski believes that the most important aspect of teaching religion, fostering a sense of empathy, can be achieved. “Rather than saying we should all believe one thing or another, or this is wrong this is right, we must understand that other people might believe different things,” Jaworski said. “We have to empathize with them.”

*Names followed by an asterix are students who have been given an alias to protect their identity.

Written by Culture Editor Alexandra Gers and Features Editor Ananya Prakash