Queer British Art 1861-1967 at the Tate Britain celebrates the 50th anniversary of the decriminalization of homosexuality. It strives to spur conversation on the fluidity of gender and sexuality of famous artists and their subjects in a time where such talk wasn’t socially acceptable. The show spans from 1861, when the sentence for sodomy was decreased in the U.K. from death to life in jail, to 1967, when sex between two consenting males was legalized.

The exhibition was separated into eight rooms. The rooms all appeared similar at first, with painted brown walls and dim lighting. All of the rooms were silent, making each step echo in a way that felt painfully loud. Art, as well as objects such as books and magazines, line the walls. This makes the exhibition interesting to even those who aren’t “into” art, as it can come across as more of a historical timeline.

The difference between each room lies in its theme. The three rooms that stood out were the first room, Coded Desires, the second room, Public Indecency and the eighth room, Francis Bacon and David Hockney. In conjunction, it is these three rooms that demonstrated the progress society’s made in accepting the fluidity of gender and sexuality.

Coded Desires is dedicated to art pieces made during the Victorian era. Considering the “prudish” reputation of the era, as stated in the show’s information pamphlet, same-sex desire seemed to be the main theme of every piece. One such piece is Simeon Solomon’s ink sketch The Bride, Bridegroom and Sad Love, which portrays a nude bride and groom. A male “friend of the bridegroom” stands next to the groom, and their embrace implies their intimacy.

Public Indecency, the second room, delves into the way sexuality and identity were both shown and hidden in public. This theme is brought to life through the use of not only art but also ordinary objects. In the center of the room, an oil painting of Oscar Wilde by Robert Harper hangs next to Wilde’s yellow prison door. Wilde, a famous playwright, poet and novelist, spent two years in jail in the 1880s for sodomy and “gross indecency”.

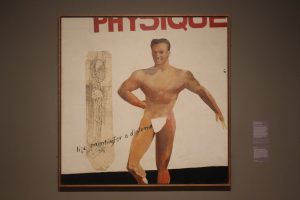

In contrast to these two rooms, the last room highlights the suggestive humor with which famous artists Francis Bacon and David Hockney covered sexuality in their paintings in the mid-1900s.

A prime example of this is David Hockney’s Life Painting for a Diploma. The oil painting shows a shirtless body builder Hockney modeled after one he saw his gay friend’s magazine. He painted the piece for his final submission at the Royal College of Art to fill his requirement for life-drawings. The playful nature of the piece, it’s focus on a homosexual model, and the fact that Hockney didn’t actually draw the model from life all show the subtle digs he made at his instructors.

Above all, the exhibition tells a story. It shows how far we have come as a society, but it also made me question why “queer” relationships had to be depicted any differently in art than heterosexual ones.

The art, although it is able to stand alone, is made even more incredible when woven into a story that draws attention to the problems that faced, and continue to face, the queer community. The art may not be as contemporary as other shows currently running in London, but the eloquence with which the exhibition tells the story of 100 years of struggle is something unique. Take any chance you have to go down to the Tate before the exhibition closes on October 1.

Written and Photos by Opinions Editor Sophie Ashley (’19)